For more than 40 years, UCLA students have been able to study, research and get hands-on experience in virtually every field of archaeology, through the UCLA Cotsen Institute of Archaeology and its affiliated curriculum on campus. In 2014, the National Research Council ranked the Cotsen’s UCLA archaeology doctoral program No. 1 in the nation.

Here are a few things you may not know about the prestigious institute.

Digital digital everywhere, (except in bones)

If you dig deep under the Fowler Museum where the Cotsen offices, classrooms and labs are located you will find sophisticated technology and data-analysis efforts in its 18 labs — which run the gamut of archaeological exploration from Andean, Egyptian and human origin labs to the zooarchaeology lab. Much of the research and vital work in modern archaeology continues long after students and faculty have left exotic dig sites behind. They regroup behind computer screens to further study their projects.

In the zooarchaeology lab or “bone lab” however, the digital world remains at bay. The ability to physically and literally compare a found specimen to the bones of a known species is still the most accurate method of identification, said Tom Wake, director of the zooarchaeology lab. Housed at Cotsen are 4,000 complete skeletons of a variety of animals — fish, lizards, snakes, birds, frogs and small mammals. This kind of dedicated collection is unique in the world and allows UCLA students and faculty immediate access to a literal physical database of bones, rather than having to go to a nearby natural history museum or archive to identify found specimens.

Items may arrive in unexpected ways

Sometimes Costen gets interesting donations from the Immigration and Custom Enforcement department of the U.S. government. When ICE agents seize illegal items from international travelers (usually collectors) that are made from the bones of an endangered species, or contain otherwise protected or prohibited materials from other parts of the world, their only options are to destroy or donate the items.

Most of these pieces are ethnographic reproductions of ancient tools or pieces of art, but they are valuable teaching tools, Wake said.

Students get to do really cool stuff (even if they’re not studying archaeology)

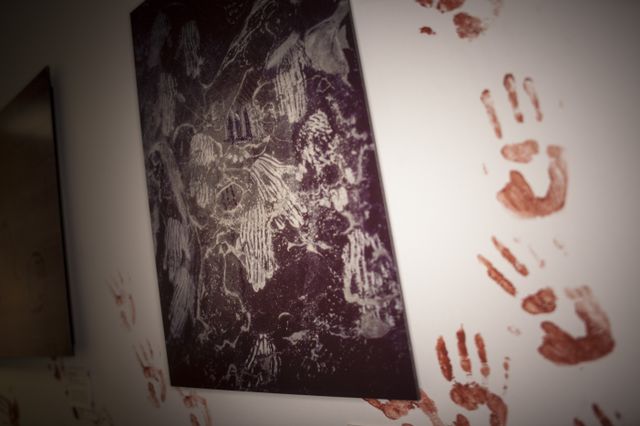

In the rock art archive in particular, work-study students from even non-archaeology courses of study, once they’ve proven themselves, get to do a lot of interesting fieldwork, the luckiest among them sometimes even accompanying Jo Anne Van Tilburg, who has served as director of the rock art archive for 19 years, on her high-profile expeditions to Easter Island.

For example, a former work-study student who graduated with a degree in cognitive neuropsychology recently received a grant that will allow him to embark upon new research into as-yet-unexplored rock art in the desert ranges of San Bernardino. The archive, which focuses on rock art in California, employs about a dozen work-study students every year, and won the Governor’s Historic Preservation Award in 2009.

Detritus matters

The work of unearthing the past is often less than glamorous. In Cotsen’s Channel Islands lab, students and researchers regularly sift through pounds of rock and sand and dirt in an effort to unveil specific debris left behind from the ancient bead manufacturing process of the Chumash Indians, who carved shells with tools made of rigid stone, and used beads as a form of currency.

Students in an “experimental archaeology” course create their own replica artifacts using only the primitive tools appropriate to the time period of piece. Much of the knowledge about how something was made comes from the debris left behind as it was made. Knowledge from debris analysis informs these craft productions.

Conservation education is big, and tiny too

Understanding the chemical and physical composition of the materials used to create archaeological artifacts and ancient art is incredibly important to conservation and preservation of them. In the conservation lab, things can get really tiny. Conservationists use powerful microscopes to examine minuscule samples of paint, or clay or textile, allowing them to uncover invaluable information on their chemical properties that will help efforts to protect and preserve artifacts as well as understand the chemical makeup of the environments they were made in.

Since 1999 UCLA has partnered with the Getty Trust for conservation education. The UCLA/Getty program in Archaeological and Ethnographic Studies is the only graduate level academic conservation program on the West Coast and the only U.S. program with a sole focus on archaeological and ethnographic materials (rather than commercial or museum art). UCLA conservation students get to study in the state-of-the art confines of a large lab located at the Getty Center.

Sharing stories and data is key

The Cotsen Institute is also home to the Cotsen Press, a publishing arm that produces around 10 academic volumes of scholarly research each year. It is one of the few programs in the United States that still does this.

And Cotsen annually produces the magazine Backdirt, which highlights recent research and activities coming specifically out of the institute. It is published each spring.

Volunteers are vital

People without academic degrees in archaeology but who have unwavering passion for the science have a natural home at Cotsen and have been a foundation of the institute since its inception. A dedicated group comprised of volunteers and consistently generous donors called “Friends of Archaeology” help create and promote public programs, assist in labs and travel with researchers to far-flung destinations.

You can get up close

Every year, Cotsen opens its doors to the public. Staff, researchers, volunteers and students will be on hand Saturday April 30 to guide guests as they explore the halls and wander into labs, and gain insight into ongoing work.

This year is the 19th Cotsen free open house. There will also be an activity area for young folks. The open house runs from 1 p.m.–4 p.m. at the Fowler Museum, A Level. Pay-by-space hourly parking is available in UCLA Lot 4.

Starting at noon is a special lecture in the Fowler’s Lenart Auditorium, with Dr. Maria Olvido Moreno, Coordinator of “Project Pre-Hispanic Mural Painting in Mexico,” Institute of Aesthetic Research UNAM, Mexico, titled “Secrets of the Feathered Object Known as Penacho de Moctezuma.”

The Fowler Museum will also be open and is free to the public from noon to 5 p.m.